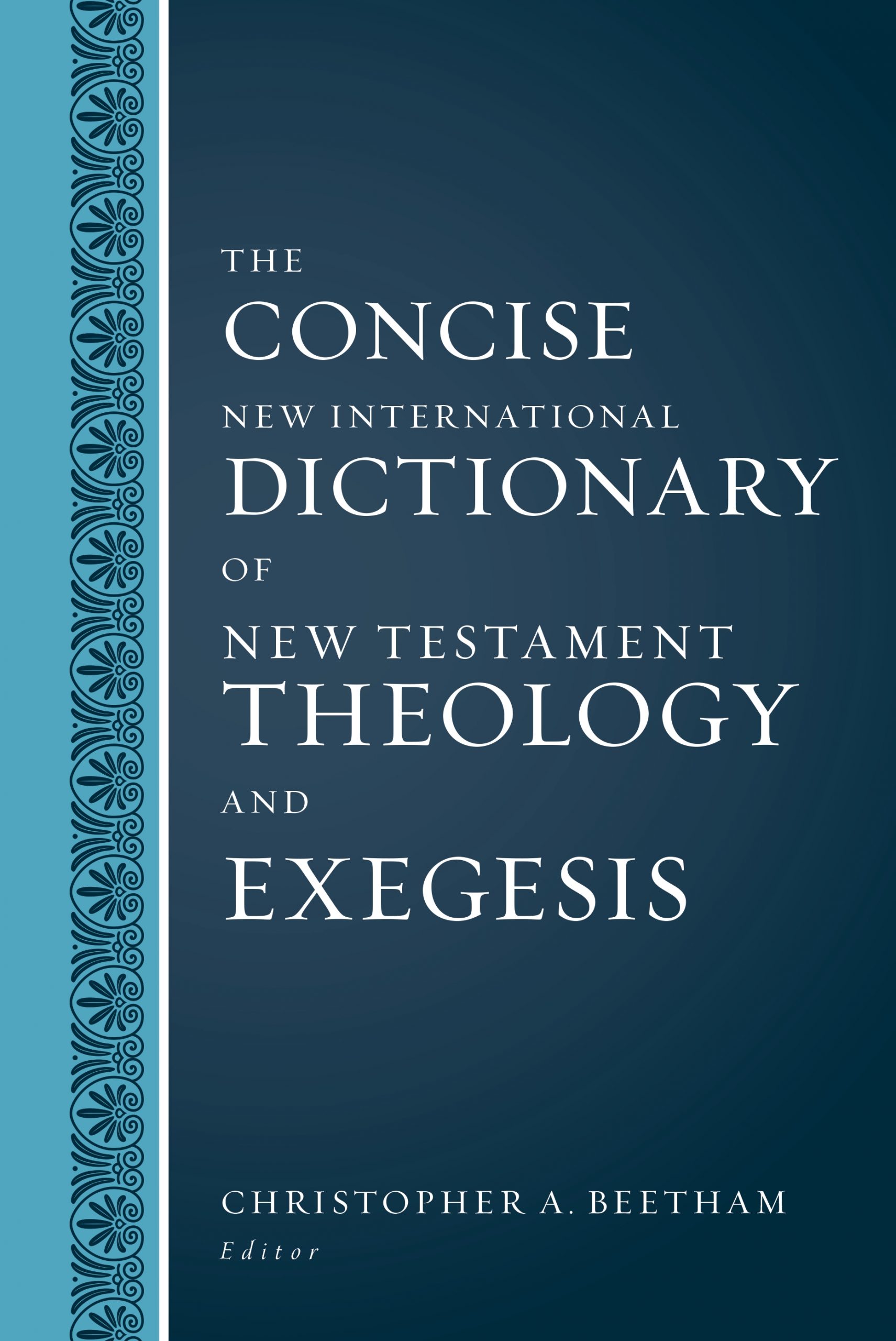

Comparing between this Concise version and the Full version here.

The present volume serves as a condensed, one-volume edition of Moisés Silva’s five-volume New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology and Exegesis, published in 2014 by Zondervan (henceforth NIDNTTE). The goal of this present volume is to make the riches of NIDNTTE accessible to a wider audience. The current volume retains approximately 55 to 60% of NIDNTTE. It differs only in the size of the articles—all the articles and features of NIDNTTE have otherwise been fully retained.1

So, what has been cut to condense the material to the size found in the present volume?

First, the bibliographies have been deleted, save for the references to the relevant material in other standard reference works, including TDNT, EDNT, Spicq, TDOT, and NIDOTTE (with occasional references to others). These references are found immediately at the end of the article.

Second, the Greco-Roman sections (labeled “GL” in the essays) are trimmed down, keeping only the most significant or relevant information. Etymological discussions were normally found here, and these have been largely removed.

Third, most discussions of the relevant terms and concepts in the literature of rabbinic Judaism have been cut. These works were written after the New Testament period (many of them centuries later), though of course many of the traditions found in these works originate much earlier than the time of composition, including the traditions found in the Mishnah (written ca. AD 200). The challenge is to know what does in fact originate from the first-century context or earlier and thus serves as relevant information for understanding the New Testament. Scholars do not doubt that the Mishnah contains material that dates to the time of Jesus and even before. The question is which material. Therefore, due to the difficult issues that surround the use of this material to understand the New Testament, the decision has been made to remove most of it.

Fourth, extended discussion of the various interpretations that scholars offer for a difficult or significant passage have been trimmed. The reader is urged to consult an academic commentary for a fuller account of the interpretive options in such cases (e.g., the Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament series).

Fifth, discussions of the use of a word in gnostic or New Testament apocryphal literature, as well as the writings of the church fathers, are normally deleted, as all these writings date later than the New Testament documents and are therefore of less value in determining the meaning of a word in the first-century context than, say, the writings of Philo and Josephus, to which references are largely retained.

Sixth, discussions of scholarly debate concerning authorship of a biblical book, putative sources (e.g., JEDP), or the authenticity or inauthenticity of a logion or pericope have been mostly eliminated except when necessary for the argument at hand. Similarly, text-critical discussions have been retained only when necessary to substantiate a significant exegetical or theological point.

Seventh, NIDNTTE often and liberally provided the reading of the biblical text for the convenience of the reader. Many of these have been deleted for economy. Yet the references have been retained so that readers can easily look up the verses for themselves should they desire to do so.